Share

To accommodate an ageing population, glaucoma management is transitioning from reactive treatment regimens to proactive ones. Three key experts detail what this mindset shift entails and how they employ it in practise.

“It’s 2024; glaucoma should not be a blinding condition.”

This sentiment by Dr Aparna Raniga, a subspecialist glaucoma and cataract surgeon at Macquarie University Hospital in Sydney, reflects a new mindset in glaucoma care. That is, casting aside the conventional reactive approach in favour of a method that proactivity manages and treats the disease before it becomes severe enough to impact on day-to-day life.

The concept – “interventional glaucoma (IG)” – is a relatively new term coined by the ophthalmic industry, and thanks to recent technological developments and landmark studies, it reflects a paradigm shift and could be the future of glaucoma management.

IG has emerged from the idea that although glaucoma cannot be prevented, blindness or significant vision loss can be slowed with early enough – and aggressive enough – intervention.

Traditional glaucoma care models involve administering eye drops – which can be associated with adverse side effects, and ocular surface and compliance issues. When ineffective, patients may then make the significant leap to conventional surgeries such as a trabeculectomy or tube shunt, which are effective but invasive, carry significant risks and require intensive follow-up.

Glaucoma and cataract expert Dr Colin Clement, of Sydney Eye Associates in Sydney, says the goal of IG is to minimise morbidity that not only results from the disease, but also its treatments.

“[IG] is all about diagnosing and treating earlier, being more proactive and perhaps using more aggressive treatments at an earlier stage in the disease,” he says. “The rationale behind this – and the primary objective of glaucoma management – is to maximise quality-of-life which we achieve through preserving vision. It’s easier to preserve vision if you can treat the disease earlier on.”

IG is an unconventional concept and glaucoma management still largely follows traditional treatment algorithms. However, momentum is building behind IG thanks to an expanding suite of diagnostic methods and the emergence of robust evidence supporting the use of more middle-ground treatments such as micro-invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS).

Another example contributing to this mindset shift is the Laser in Glaucoma and Ocular Hypertension (LiGHT) study published in 2019. In this landmark trial, a comparison between selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) and eye drops identified SLT as having a similar efficacy profile to eye drops when used as first-line treatment, but with improved quality of life, and a greater reduction of adverse side effects and additional surgical requirement.

Raniga acknowledges the benefits of early intervention with SLT and says there needs to be a shift away from administering eye drops, as they have the potential to complicate other treatment interventions.

“SLT bypasses the side effects of drops, and issues with adherence and compliance. It’s effective, and it’s also safe. So, I’m certainly offering and performing laser treatment earlier,” she says.

“Patients who’ve been on drops for decades tend to have much more scarring potential, no matter which surgery they have. Long term studies have demonstrated that the effectiveness of a trabeculectomy for a patient who has been on drops for decades is not as good as a trabeculectomy that’s done early.”

Early and aggressive intervention for Raniga often entails a discussion of eye drops and SLT with early disease, or eye drops and SLT with surgical intervention if the disease is advanced.

New surgical opportunities

Contributing to IG’s growing support is the proliferation of MIGS on to the treatment landscape. First introduced in 2010, it works to treat mild- to-moderate disease and bridges an important gap.

“MIGS has emerged to fill a treatment gap that exists between medication, laser and surgery, because in terms of risk for the patient, there’s a large step up when undertaking surgery,” Clement says. “The reason it fills that gap is because it’s very safe, so the risk to the patient is fairly low.”

Clement says, in his experience, patients who do not adequately respond to medication or laser can achieve the pressure reduction they need with MIGS, as opposed to the traditional invasive glaucoma surgery.

“There is the possibility that MIGS can be used earlier in the treatment paradigm and there’s even the possibility that it could be used as primary treatment,” he says.

One barrier to early uptake, Clement says, is patient selection. Information regarding which patients respond well to MIGS and which do not is still being collected. As patient selection improves, surgeons will be able to offer MIGS with greater confidence of achieving a positive outcome.

“Currently, MIGS is performed in a day surgery setting or hospital and there’s time and cost associated with that. One thing that would be a real game changer is if these procedures could be offered as a treatment in clinic so there’s no inconvenience to the patient. It’s quick and makes it considerably more cost effective.”

The data shows the current crop of MIGS devices appear to boast ideal safety and efficacy profiles. Ongoing evidence is available, with safety and efficacy constantly monitored so surgeons and patients can be confident they’ll deliver the desired results.

Glaucoma and cataract surgeon Associate Professor Mitchell Lawlor of Sydney Eye Surgeons, has been influential in capturing some of this data through the Fight Glaucoma Blindness! (FGB) registry at the Save Sight Institute.

The registry serves to compare ‘real-world’ safety and efficacy outcomes of devices released to the market. Specifically, it tracks iStent inject surgeries, Xen implants and conventional glaucoma surgeries such as trabeculectomy and tube shunts.

In the case of the CyPass Micro-Stent, where concerns of corneal endothelial cell damage emerged after five years of follow up, the significance of registries such as FGB cannot be understated. Although the CyPass has since been voluntary withdrawn, Lawlor says the other devices are still showing a favourable safety and a good efficacy profile over time.

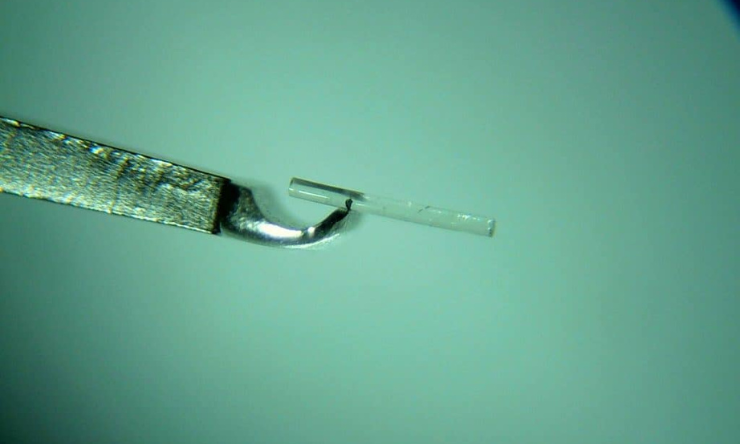

iStent inject and the Hydrus Microstent, are the two most-used MIGS devices and have Medicare reimbursement as both a standalone procedure, or combined with cataract surgery. The newly available MINIject, alongside the Xen device also come under this category.

“Some of the new devices that have been offered have had a pretty quick uptake given how they’re only recently come to market in the last decade, but they’re already playing quite a big role in our treatment,” Lawlor says.

iStent inject is one example. Commercially, it has been around the longest in Australia and thus has the most evidence to support its use.

A 2022 study by Clement, Lawlor and their colleagues explored the 24-month safety and efficacy profiles of iStent inject and Hydrus in combination with cataract surgery. The devices demonstrated sustained IOP reductions and good safety profiles.

“I think that also allows surgeons to have comfort the procedures should be part of their repertoire,” Lawlor says.

Raniga says there is still work to do in catching the disease early, including identifying high-risk patients through family history of glaucoma.

“Understanding the individual patient’s risk profile really helps with proactively treating those fast progressors. In patients with greater risk factors, such as those who have a strong family history of glaucoma, it is vital to check their rate of progression more closely,” she says.

“For those patients, I think we should definitely intervene much earlier because we’re hopefully going to prevent that end-stage glaucoma that we want to eliminate and to maintain a good quality of life.”

Lawlor says that for wide adoption of MIGS and earlier intervention, data captured through the FGB registry will help to understand which subgroups of patients most benefit from which type of device. This information will allow more targeted invention in the group of patients most likely to benefit.

Tackling a rising prevalence

While there are upsides to IG, increased testing, OCT access, genetic testing, potentially more surgeries and the manpower to oversee all of this could place more pressure on an already-stretched glaucoma care system.

“[IG] is a concept that’s very much suitable for a health system that’s highly resourced. So, if you tried to apply this to a system that’s not, it would be very challenging,” Clement says.

With an ageing population, and with more earlier diagnoses, the capacity of ophthalmologists to sustainably service this population also comes into question.

“If you’re seeing more patients and intervening earlier, and with an ageing population, the overall number of patients we’re treating is going to increase, which raises issues about capacity to serve patients. Collaborative care could potentially help with that,” Clement says.

“This care model may entail optometrists taking on a greater role in managing stable patients, with a shift toward ophthalmologists providing more of a ‘surgical’ service.”

With early diagnosis holding the key to greater IG uptake, primary eyecare providers, who see a wide scope of patients, hold the key to timely referrals.

Additionally, Lawlor believes collaborative care models are also useful when monitoring disease progression.

“We work together as professionals to make sure that patients are monitored over time, with a cohort who may well have a lower risk of progression given they’ve had a glaucoma intervention,” Lawlor says.

Ultimately, he says that transitioning to an IG model requires consideration of risk and patient suitability.

“While early intervention is beneficial in those patients who are likely to develop significant vision loss, there is a risk that it could lead to over treatment of some patients. We therefore need to continue refining methods of stratifying those who are at higher risk of progression to determine which patients need early intervention.”

This article has been republished courtesy of Insight