Share

The important issue of driving in patients with Glaucoma comes up often. Most of us drive all the time without thinking too much about it, and for most people it is very difficult to go about our daily lives without it.

The fact that Glaucoma is asymptomatic until late in the disease, means people can have serious visual impairment which puts them at increased risk of a car accident without actually being aware of it.

Blind spots (“scotomas”) in the vision caused by Glaucoma are initially asymptomatic because our brains ‘fill in the gaps’. For those familiar with looking at visual field printouts which show blind spots as black patches, this is not what the patient actually sees. What the patient actually sees is what they think is a view of the world as they normally would but certain objects within that visual field are missing or not seen.

If the blind spots from the corresponding parts of the vision in each eye overlap then this can cause a blind spot even with both eyes open. This has been shown to increase the risk of collisions on the road.

The levels that are currently required for driving are set out in Austroads National guidelines (“Assessing fitness to Drive”), The guidelines are quite detailed (260 odd pages!) and are available online. https://austroads.gov.au/drivers-and-vehicles/assessing-fitness-to-drive. This is reviewed from time to time by a panel of experts, and the latest version was released in 2022. Glaucoma Australia made a submission on behalf of Glaucoma patients at the time the guidelines were up for public consultation. These guidelines stipulate all conditions for driving, and there is a dedicated section on vision.

The act of driving is a complex set of behaviours that we perform automatically. For some people with glaucoma, the ability to ‘see something out of the corner of your eye’ which could prevent you from having an accident may be lacking.

Commercial drivers are subject to different regulations compared to those holding a private licence. For private licence holders, the vision requirements for driving are:

- Visual acuity of 6/12 or better with both eyes open (with or without glasses)

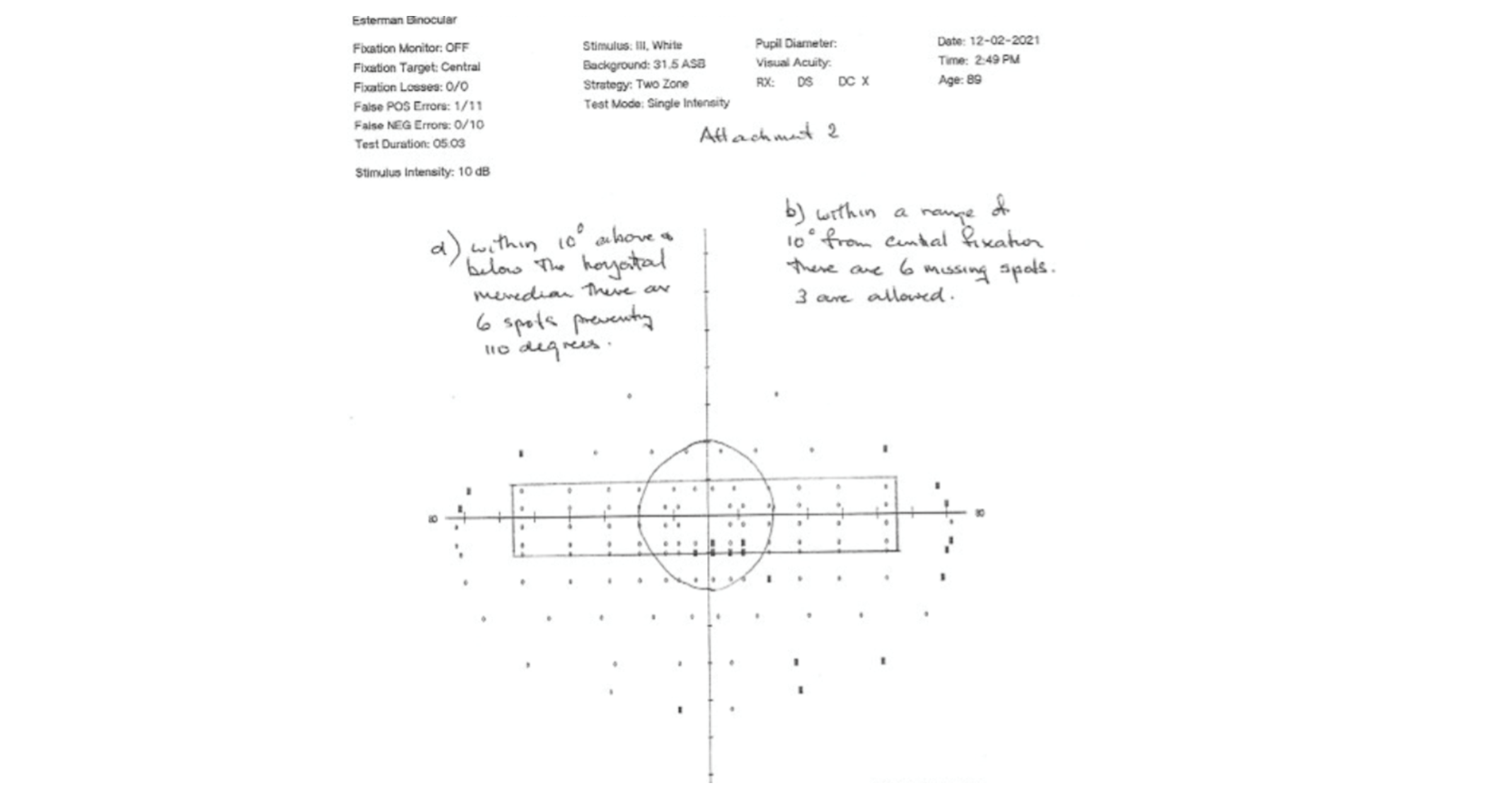

- Visual field of at least 110 degrees in horizontal extent

- No ‘unacceptable scotoma’ (cluster of 4 or more points) within the central 20 degrees of vision

- No significant double vision

The Esterman test is used to assess the visual field for driving. This is a specific setting on the visual field machine and is performed with both eyes open. It’s important to note that this differs from the standard visual field test commonly used to assess glaucoma, which typically tests each eye separately.

If you need a visual assessment for your driver’s licence and forms completed, it’s a good idea to let your eye care provider know in advance, as this may require an additional visual field test.

Here is an example of an Esterman test done for driving. We have marked the area showing how far the horizontal vision needs to reach, as well as the central area where large blind spots are not allowed. In this case, the patient’s horizontal field was 110 degrees, but they did not meet the vision requirements because of a large blind spot within the central 20 degrees when tested with both eyes open.

The current guidelines stipulate the Esterman test be used in visual field assessment. While no system is perfect it provides a reliable, standardised way to assess whether someone meets the legal vision requirements for driving. It focuses on the parts of the visual field most important for safe driving, particularly the ability to detect hazards and see to the sides while looking straight ahead.

Understandably, it can be very difficult for patients who don’t meet these requirements. Being told you are unfit to drive can be upsetting and confronting, especially when it affects your independence. It’s helpful to know that clinicians aren’t judging you or your driving ability. Instead, we use clear, objective guidelines to check if your vision meets the safety standards needed for driving as determined by the licencing authorities.

In some cases, it may be helpful to voluntarily raise any vision concerns that could impact on your driving. Doing so early can help manage expectations and may allow for a smoother transition, rather than facing a sudden and unexpected outcome. That said, it’s not uncommon for patients to be unaware of their responsibility to report vision issues to the driver licensing authority, even though there is a legal obligation to do so in many regions, including NSW. Other states also have mandatory reporting obligations on practitioners.

Some common misconceptions and frequently asked questions:

1. Do different states have different rules with regards to vision and driving?

No - the Austroads guidelines apply and are the same across all states and territories. However, because licenses are issued by the individual states, the process for how these rules are assessed may differ in each state.

For example, in NSW everyone aged 75 and over receives a letter each year asking them to have medical certification that they are fit to drive. This can be done by their GP, who handles the general medical clearance. However, a special vision section on the form can be completed by an Ophthalmologist or Optometrist if the GP has insufficient information to assess vision. Additionally, anyone with an eye condition (like glaucoma) must declare it when renewing their licence. If they do, they’ll need a medical review every two years, even if they’re under 75.

2. How come someone can drive with only one eye, and I have two eyes but still don’t meet the requirements?

Someone with one healthy eye can still meet the vision requirements for driving. That’s because one eye on its own can usually see clearly and has a wide enough field of vision.

It’s a common misunderstanding that each eye only sees one side—left eye sees left, right eye sees right. In reality, each eye sees most of the visual field, with a large overlap in the middle.

If one eye is lost but the other is healthy, the person will still see almost everything, except for a small missing area on the far edge, on the side of the blind eye.

With glaucoma, the problem is different. Even when both eyes are open, vision can be worse if the glaucoma is advanced than someone with just one healthy eye. That’s because the areas of vision loss in each eye can overlap, creating bigger blind spots in the overall field of vision.

3. How come I can read the chart perfectly and not be fit to drive?

Being able to read the chart tests visual acuity—that’s your sharp, central vision used for reading and seeing fine detail. But that’s only one part of what’s needed for safe driving.

Glaucoma usually affects your peripheral (side) vision first, not your central vision. So, even if someone has significant vision loss in their outer field of vision, they might still read the chart perfectly.

To be fit to drive, you need both:

Good visual acuity (sharpness), and

A wide enough horizontal field of vision—what you can see out to the sides when looking straight ahead.

In glaucoma, it’s often this loss of peripheral vision that becomes the problem, and people don’t always notice it themselves.