Share

Lowering intraocular pressure (IOP) via eyedrops, laser treatment or surgical intervention remains the gold-standard for glaucoma treatment, however there is increasing interest and research in the role of exercise on glaucoma development and progression. To fully understand the impact of exercise in glaucoma patients, it is firstly important to understand that there are different types of exercise.

AEROBIC EXERCISE

Aerobic exercise, also commonly referred to as “cardio”, encompasses activities that are generally low-to-medium intensity and of relatively long duration (greater than 2 minutes). This includes walking, swimming, jogging, cycling and gardening. There is a high level of consensus in the literature that a moderate degree of aerobic exercise on a regular basis (approximately 3 times a week) has a beneficial effect on IOP.1-6 The baseline IOPs of individuals who performed moderate exercise on a regular basis have been reported to be lower than those who led sedentary lifestyles.3 Moreover, studies have found temporary reductions in IOP following aerobic exercise, although measurements tended to return to baseline after 40 minutes.3 Interestingly, people who self-reported low fitness level or previous sedentary lifestyles seemed to generate the greatest reduction in IOP once they increased their levels of aerobic activity, although this effect gradually tapered off as they became conditioned to exercise.3-5 This is supported by a small study of 90 patients conducted in 2015 – patients who were newly diagnosed with glaucoma seemed to show a greater reduction of IOP when recommended eyedrops as well as 30 minutes of aerobic exercise a day, as opposed to those who were prescribed eyedrops only.7

In addition to IOP reduction, moderate levels of aerobic activity improve blood flow to the optic nerve head and support healthy nerve function, can help contribute to a healthy BMI (in conjunction with diet), and likely have a positive impact on mood and stress. Studies have established a positive correlation between IOP and BMI as well as muscle-to-fat mass ratio, wherein patients with greater BMI and/or greater fat mass tended to have higher IOPs; and those with lower BMI and/or greater muscle mass tended to have lower IOPs.8 Moreover, the diagnosis of a chronic and potentially vision-threatening condition can have a significant impact on an individual’s mental health and bring about symptoms of depression or anxiety. Therefore, aerobic exercise in glaucoma management may serve more than one benefit – that is, it can improve IOP control as well as quality-of-life, both from a physical and psychological point of view.

While swimming is considered an aerobic form of exercise, swimming with tight-fitting goggles has been identified as a cause of temporary IOP elevation.1,3 There is some debate as to whether this is only significant in patients with established glaucoma as opposed to normal individuals.5 IOP tended to normalise after removal of the goggles, nonetheless in patients with moderate-to-severe glaucoma it is generally recommended to avoid tight-fitting elastic bands and eye pieces.3

ANAEROBIC & ISOMETRIC EXERCISE

At the other end of the scale, anaerobic activities that are high-intensity and short-duration (less than 2 minutes) such as weight-lifting, sprinting and interval training may be associated with a greater prevalence of glaucoma and this could be due to increased oxidative stress and inflammation.5 Additionally, isometric activities are a specific form of anaerobic exercise which involves holding a certain position to contract a specific muscle or muscle group. The goal of isometric exercise is to build muscle strength in a similar way to weightlifting.5 Isometric exercises and weightlifting have been known to transiently increase IOP by up to 4-5mmHg, although there is a fairly rapid return to baseline once ceased.4,6

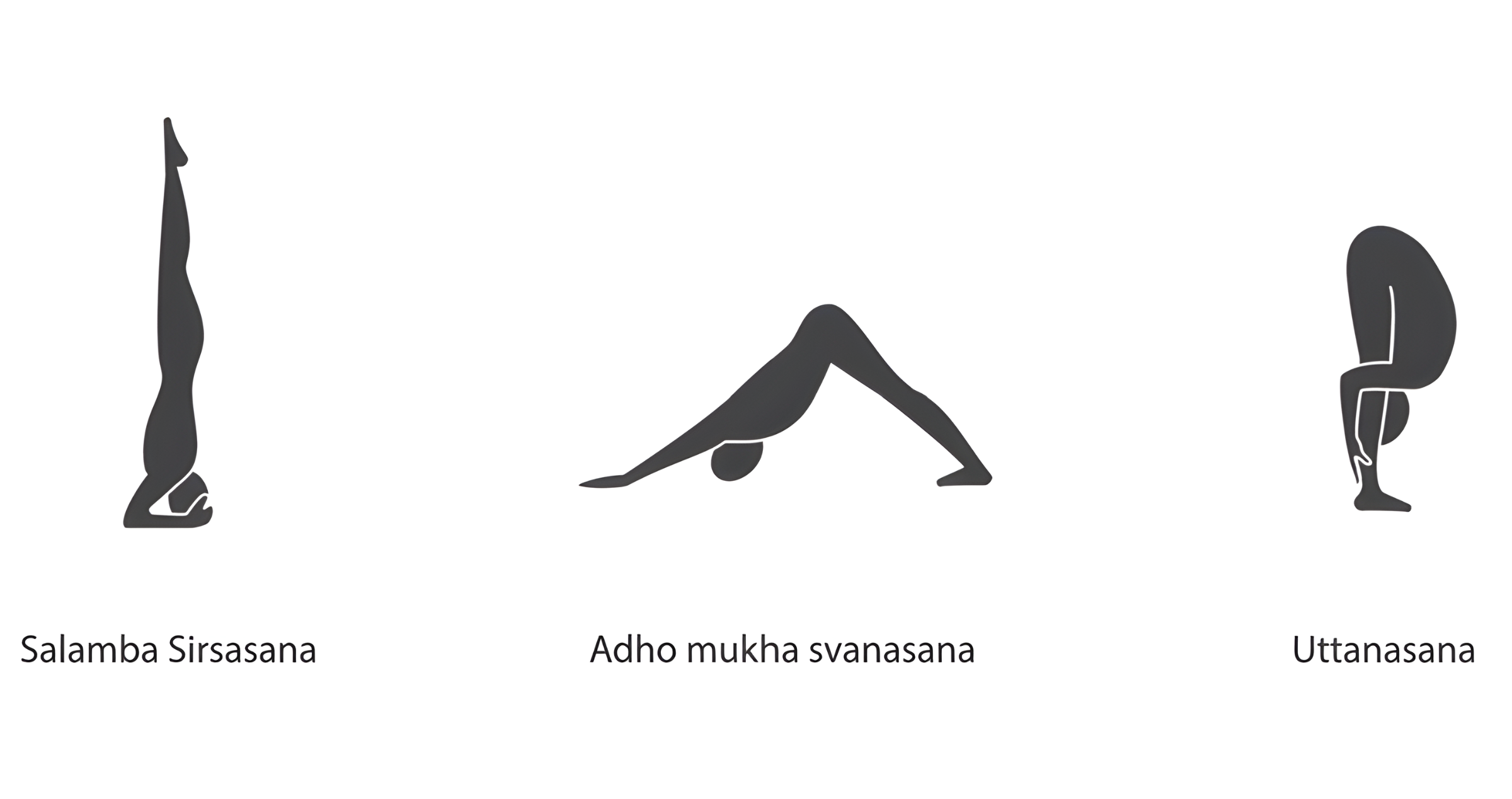

Yoga not only incorporates isometric exercises, it can also involve head-down positions such as Salamba Sirsasana (supported headstand), Adho Mukha Shvanasana (downward facing dog) and Uttanasana (forward fold) (Figure 1) that can cause transient elevations of IOP as high as 11-16mmHg.1,2,4 Again, return to baseline IOP is generally fairly rapid (approximately 5 minutes),4 nonetheless in patients with evidence of progressive glaucoma and/or moderate-to-severe glaucoma it may be worth looking at amendment of isometric exercises and yoga practices to minimise the risk of temporary IOP elevation.

Figure 1. Salamba Sirasana (supported headstand), Adho Mukha Svanasana (downward facing dog) and Uttanasana (forward fold) poses in yoga can cause transient elevations of intraocular pressure (IOP) and should be performed with caution in patients with established glaucoma, particularly if there is evidence of progression despite good seemingly good IOP control.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, a moderate amount of aerobic activity on a regular basis is likely to optimise IOP and lower the risk for glaucoma development and progression, as well as promote improved mental health and general well-being. Patients who are adopt a holistic management plan for glaucoma (incorporating conventional IOP lowering treatments as well as exercise and lifestyle modifications) not only gain the aforementioned benefits but also tend to report improved feelings of control over their glaucoma, fewer symptoms and less concerns as opposed to those who were prescribed eyedrops only.9 Care should be taken with anaerobic and isometric exercises, particularly yoga and head-down positioning, particularly in patients with established glaucoma.

Certain patients or certain types of glaucoma may warrant more specific advice (for example, IOP elevation following exercise may be more common in a sub-type of glaucoma known as pigment dispersion glaucoma) – as always, if you have questions regarding exercises or activities that you perform and the impact this may have on your glaucoma, please speak to your treating ophthalmologist or optometrist.

REFERENCES

1. Fahmideh F, Marchesi N, Barbieri A, Govoni S, Pascale A. Non-drug interventions in glaucoma: Putative roles for lifestyle, diet and nutritional supplements. Survey of ophthalmology 2021.

2. Hecht I, Achiron A, Man V, Burgansky-Eliash Z. Modifiable factors in the management of glaucoma: a systematic review of current evidence. Graefe's archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology 2016; 255: 789-96.

3. Moreno-Montañés J, Antón-López A, Duch-Tuesta S, Corsino Fernández-Vila P, García-Feijoó J, Millá-Griñó E, Muñoz-Negrete FJ, Pablo-Júlvez L, Rodríguez-Agirretxe I, Urcelay-Segura JL, Ussa-Herrera F, Villegas-Pérez MP. Lifestyles guide and glaucoma (i). Sports and activities. Archivos de la Sociedad Española de Oftalmología (English Edition) 2018; 93: 69-75.

4. Pasquale LR, Kang JH. Lifestyle, Nutrition, and Glaucoma. Journal of glaucoma 2009; 18: 423-8.

5. Perez CI, Singh K, Lin S. Relationship of lifestyle, exercise, and nutrition with glaucoma. Current opinion in ophthalmology 2019; 30: 82-8.

6. Stewart WC. The effect of lifestyle on the relative risk to develop open-angle glaucoma. Current opinion in ophthalmology 1995; 6: 3-9.

7. Agrawal A. A Prospective Study to Compare Safety and Efficacy of Various Anti-Glaucoma Agents and Evaluate the Effect of Aerobic Exercise on Intra-Ocular Pressure in Newly Diagnosed Primary Open Angle Glaucoma Patients in a Tertiary Care Hospital. Value in health 2015; 18: A415-A.

8. Kim HT, Kim JM, Kim JH, Lee JH, Lee MY, Lee JY, Won YS, Park KH, Kwon HS. Relationships Between Anthropometric Measurements and Intraocular Pressure: The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. American Journal of Ophthalmology 2017; 173: 23-33.

9. Hecht I, Achiron A, Bartov E, Maharshak I, Mendel L, Pe'er L, Bar A, Burgansky-Eliash Z. Effects of dietary and lifestyle recommendations on patients with glaucoma: A randomized controlled pilot trial. European journal of integrative medicine 2019; 25: 60-6.