Share

As useful as it can be, performing OCT on every patient who walks through the doors of a primary eyecare practice is a double-edged sword that poses significant challenges and limitations. Although OCT is excellent at improving understandings of ocular disease and makes ‘refined phenotyping’ possible, previous research has shown that it is also associated with a higher rate of false positives and an increased tendency to refer.

These factors can be problematic, especially in the public healthcare system where waiting times for a non-urgent routine ophthalmic appointment typically already exceed three months.

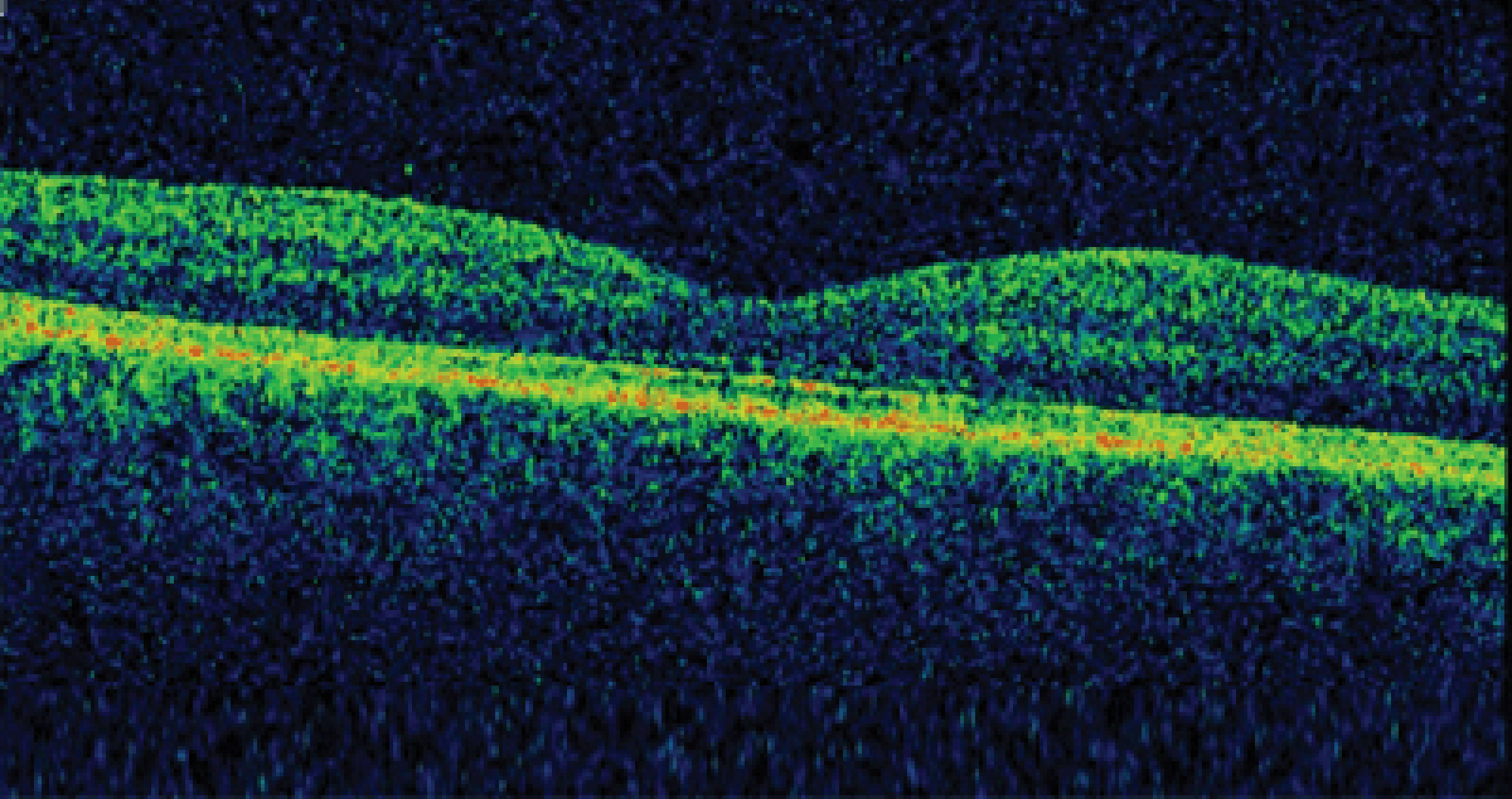

Thanks to its speed, convenience and micrometre scale resolution, it comes as no surprise that OCT has become a mainstay of primary eyecare in developed nations like Australia.

However, we are arguably at a crossroads regarding its use in clinical practice. Should it be applied en masse; that is for the indiscriminate, opportunistic screening of all patients presenting for an eye examination? Or alternatively, in a more judicious, targeted manner as a supplementary, diagnostic procedure?

This is an issue that I examined with co-authors, Professor Michael Kalloniatis, Dr Jack Phu and Ms Paula Katalinic in our paper An evidence-based approach to the routine use of optical coherence tomography, published earlier this year.

General Trends

The current application of OCT ‘screening’ varies, but I see three general approaches emerging today: The first is general population screening in a non-targeted manner, whereby the goal, in theory, should be to identify patients with or at high risk of sight loss and benefit them in some way through an effective intervention. This approach is contingent upon a reference standard, as well as strict criteria for normal versus abnormal.

The second is targeted screening, which involves the screening of a selected sub-population according to prior knowledge of the characteristics or behaviours that place individuals at increased risk. Such categories include high-risk sub-populations and outreach settings to promote equity and better reach individuals with undiagnosed eye disease. This is the approach that I most endorse.

The third obvious trend is opportunistic screening, which describes the application of screening within a routine health service, such as in a primary care medical practice setting, and not as an organised program. This could include a form of pre-testing on all individuals that present for health care, regardless of the reason for presentation.

I see several issues relating to the use of OCT as a screening tool. Some of the limitations are practical, such as their cost and the surrounding IT infrastructure, while some are inherent to the devices. For example:

- Cost: Currently the availability and affordability of OCT varies depending on geographic and socio-economic circumstances. Public versus private health care settings is one such example. Low cost, portable OCT devices are being developed but will need further validation.

- Difficult to interpret: A routine OCT volume scan might include, for instance, 128 B-scans per eye. Given an average primary eye care professional might see 15 patients per day; this means an overwhelming 3,840 scans need to be reviewed daily. Inspecting these scans is both time and expertise intensive. Substantial time also goes into keeping updated with the latest evidence. Additionally, many diseases and signs can only be determined through careful evaluation and in combination with a full clinical assessment. For example, all patients who convert to late age-related macular degeneration (AMD) show drusen regression as a preceding event. Yet a cursory glance of OCT findings in isolation is unlikely to reveal these signs. Of greater concern is that these events may go undetected if the clinician doesn’t look for th.

- Not all eye disease detectable with OCT may be treated: Screening should take into consideration whether further action (e.g. therapeutic treatment) is available to mitigate the individual’s overall risk of vision loss, as well as other factors such as the local health care system and workforce constraints.

- Existing informative technology infrastructure is prohibitive: A single OCT scan represents a large composite of A-scan (reflectivity) data. Databases are currently being developed, but these information systems will require further development to better support OCT information.

- Most importantly, the potential high rate of false positives: An ideal screening test minimises the risk of anxiety to the individuals screened by balancing a high detection rate of true positives against a low level of false positives.

If OCT is used purely in isolation, in a pool of 10,000 patients there will be 340 with glaucoma. If OCT is applied in isolation to all of them, 483 normal patients will be misdiagnosed as glaucoma and 68 will be missed – assuming a sensitivity and specificity of 80% and 95% respectively.

The likelihood of OCT returning a positive result is equal to the proportion of true positive patients with disease over the sum of true positives and false positives: 36%.

As the gatekeepers of the eye care system, healthcare providers are in the best position to convey this information to patients and mitigate the tide of over-diagnosis and misinformation.

Translating Early Detection To Better Outcomes

We want the best for our patients and have been taught to manage patients holistically, constantly looking out for the bigger picture. But what impact does OCT ‘screening’ really have on our patient’s eye health?

It is easy to assume that because these tools are good, then we should apply them more often. But the cost, complexity, time and expertise intensive nature of OCT indicate it would be best applied as a supplementary, diagnostic device in a highly targeted manner.

One form of achieving this is via an intermediate-tier level of care situated between primary optometric care and specialist ophthalmological care.

This Centre for Eye Health model is currently operating out of Sydney and recently expanded to a satellite location in the Sutherland hospital. It provides a refined model of collaborative care integrating a team of 15 optometrists, the local academic institute – the University of New South Wales, Sydney – and public hospital ophthalmology.

We have shown that the application of OCT delivered in this type of clinical setting successfully reduces the number of false positive cases and cases without a known diagnosis. The question begs: we can, but should we? Widespread application of OCT for disease screening is a tempting notion but it should be held to the same scrutiny as any medical procedure and the benefits carefully weighed against the risks.

For a test to be useful, the pass-fail criteria should be well-defined and the disease ‘screened for’ should be targeted. The application of OCT should be evidence-based and considered in conjunction with other aspects of the clinical examination.